http://www.inq7.net/globalnation/sec_phe/2004/jun/23-03.htmBy Augusto F. Villalon

Inquirer News Service

A PIONEERING partnership by the Department of Education (DepEd) and the Heritage Conservation Society (HCS) has been implementing the Heritage School Building Restoration Program.

Originally conceptualized by former Education Secretary Armand Fabella and later by his successor, Brother Andrew Gonzalez, the program is now being put into motion by Education Secretary Edilberto de Jesus and Undersecretary Juan Miguel Luz.

DepEd and HCS will identify and restore one heritage schoolhouse in each region of the country. HCS will then organize a consulting team to provide the restoration and technical expertise and oversee the restoration together with DepEd engineers.

The first to be completed is the historic Rizal Elementary School in Bacolod. The renovated structure was inaugurated last Saturday, June 19, the birthday of the national hero Jose Rizal.

The program restored the Rizal Elementary School building to as close as it could get to the original state. Set back from the street by an elegant tree-shaded plaza, the two-story building was typical of those constructed during the era. However, insensitive remodeling over the years altered the interior of the 1907 building. Finally it was abandoned and left to deteriorate.

Its original construction of wood supported by a concrete base survives. A verandah wraps around the ground floor and an old acacia tree shades its open second story.

Large sliding kapis windows above ventanillas that reach to the floor open up large sections of wall to the outdoors. To maximize the interior airflow, interior partitions have rows of pierced wooden fretwork (calado) panels that meet the high ceiling, allowing air to freely circulate within the building.

Its high-pitched, galvanized-iron roofing sweeps way past windows and walls with a generous overhang that shades the building and keeps rain away.

Attuned to the tropics, the building is breezy and cool. Being inside the restored building today proves that old-style tropical architecture is still the best for our climate. Mature shade trees cool the breeze that once again flows through the large windows.

The restored building shows that instead of being rendered obsolete, old structures can still be recycled for modern academic uses. The ground floor of the newly restored building will house a state-of-the art computer laboratory, a music room, and administrative offices. The first-rate library that Rizal Elementary School deserves will occupy the entire second floor.

The rationale behind the program is to make history come alive for teachers and students by recycling historic structures not as ivory-tower museums but as classrooms and laboratories for everyday use. The program projects heritage as touching all aspects of daily life, not as an irrelevant, elitist notion as the common misconception has it.

Now that teachers and students will once again use the heritage building, the history of the Rizal Elementary School and the DepEd comes back to life, making the public aware of the heritage of the school and of the DepEd's legacy of nation-building through literacy.

Originally founded in 1901 as the Instituto de Rizal, the school was renamed the Rizal Institute in 1903 when the American Thomasite teachers arrived in Bacolod. When it transferred to the present building in 1907, it became Bacolod High School until 1924, when it changed name to the Occidental Negros High School.

It was converted into Bacolod West Elementary School in 1932, and was renamed Rizal Elementary School in 1959.

The tradition of mass education in the Philippines started in 1901 when 1,074 American teachers sailed to our shores aboard the transport ships Thomas and Sheridan. Since the majority of them arrived on the Thomas, they were called the Thomasites.

The Thomasites quickly fanned all over the country, setting up schools in far-flung localities where no school facilities existed.

Representative Isauro Gabaldon authored Act 1801 of the National Assembly, which allocated P1 million for the construction of elementary schools all over the country. The buildings are generically called Gabaldon Schoolhouses.

Yale graduate William Parsons, the consulting architect of the Bureau of Public Works from 1905-1914, prepared a set of standard designs for one-story buildings that were slightly elevated above ground, with classrooms along one side of an open gallery. Nipa roofs recalled the bahay kubo and so did the swing-out windows with kapis panels.

To celebrate the DepEd's century of existence, the program will restore different types of school buildings typical of the American colonial era when the public-education program in the Philippines was a high government priority.

Scheduled for completion in October is Baguio Central School.

Heritage studies are not formally offered in most universities. To introduce heritage to the university curriculum, the HCS is coordinating teams of history, engineering and architecture students from Manila and Baguio universities to document the heritage structures in Teachers Camp in Baguio.

The student involvement will lead to the preparation of architectural plans by conservation professionals for most of the Teachers Camp structures.

By restoring classrooms, the DepEd drives home the lesson that patrimony lives and continues to be relevant to our lives. Classes in heritage classrooms provide experiential learning on patrimony with a stronger impact than textbook instruction.

E-mail your feedback to afvillalon@hotmail.com

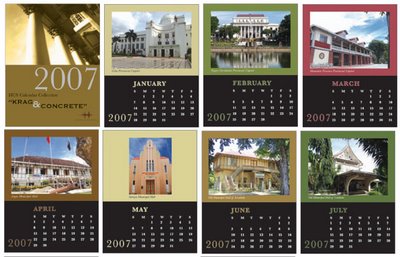

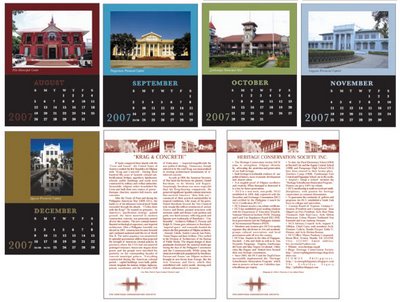

The 2007 HCS Calendar featuring heritage provincial capitols, city halls and municipios, is now on sale. For more information, contact:

The 2007 HCS Calendar featuring heritage provincial capitols, city halls and municipios, is now on sale. For more information, contact: