http://news.inq7.net/regions/index.php?index=2&story_id=70904By Tonette Orejas

Philippine Daily Inquirer

THESE buildings are called the Gabaldon. Three, perhaps more, generations of Filipinos learned the Three Rs (reading, ’riting and ’rithmetic) in what are now regarded as the “Parthenon” of the golden years of Philippine public education system.

The structures count by the thousands and are spread out all over the archipelago, with some towns or cities having two or more.

Almost a century since Assemblyman Isauro Gabaldon of Nueva Ecija in 1907 authored Act 1801 that set aside P1 million for their construction, the buildings—many of them run down by time, the elements, looting and neglect—are enjoying a restoration boom with a strong thrust for conserving the original, functional design.

Yale graduate William Parsons, the consulting architect of the Bureau of Public Works from 1905 to 1914, designed the school buildings that were later named after Assemblyman Gabaldon.

The Department of Education and the

Heritage Conservation Society (HCS) are leading efforts through the heritage school building restoration program.

“Pioneering” is how architect Augusto Villalon of the HCS calls the partnership.

The idea, Villalon said in a recent column in the Inquirer, came from former Education Secretary Armand Fabella, and was pushed by his successors, the late Br. Andrew Gonzalez FSC and Edilberto de Jesus, as well as Undersecretary Juan Miguel Luz.

The program has completed the restoration of the Rizal Elementary School in Bacolod City, the Pampanga High School in the City of San Fernando in Pampanga, and the Baguio Central School in Baguio City, according to HCS member

Ivan Anthony Henares.

Up for restoration are the West Central Elementary School and its adjacent home economics building in Dagupan City, said Henares, who has created a web log or blog (

gabaldon.blogspot.com) to link individuals, groups, institutions and donors to the effort.

“The sheer number of Gabaldon schools all over the country and the lack of funds to restore these buildings would not make it possible to include all in the program,” he said.

Heritage resourcesThe buildings are “an inherent part of our country’s heritage resources,” he said.

The project has the support of the locals.

In Naga City, Councilor Lourdes Asence has authored a proposed ordinance that seeks to create a task force for the preservation and restoration of all historical structures, including six Gabaldon buildings in that city and in Camarines Sur.

In Bohol, the provincial government spent P2.5 million in 2004 to repair some of its Gabaldon buildings.

In their respective websites, historians in Infanta, Quezon, and in Leganes, Iloilo, have cited the history of their towns’ Gabaldon buildings and their impact on the people’s education.

Party-list Rep. Florencio Noel (An Waray) has filed House Bill No. 4392 proposing the rehabilitation and repair of Gabaldon school houses nationwide to “preserve their historical significance and to address the need for more school buildings.”

History

Some have indeed etched their place in history.

For instance, the Gabaldon building in Dagupan became a temporary residence of American Gen. Douglas MacArthur during World War II, according to Carmen Prieto, chair of the city’s heritage commission.

Others served as hospitals, town halls or evacuation centers in times of war and calamities.

More importantly, it was in the rooms, libraries and wide grounds of the Gabaldon buildings that American and Filipino educators helped unlock the potentials of students, many of them poor.

The Pampanga High School, for one, nurtured many of the country’s leaders like the late President Diosdado Macapagal (Class 1929).

But perhaps one of the most poignant memories of the Gabaldon and a vivid description of the edifice comes from one who passed through its halls.

Former Quezon Board Member Frumencio “Sonny” Pulgar, in his website, said that as a student, he was a habitué of the “Gusaling Gabaldon” or “Bagong Iskul,” the elementary school in his hometown of Calauag.

“For me, Gabaldon was the biggest edifice I had ever seen and played in,” he said.

“True, it is not a multistory structure; in fact, it’s a mere one-story affair, but I looked at it with awe. Its ceiling was high, about five meters. I thought giants walked through the corridors of Gabaldon. It had a long five-tread flight of stairs leading to its elevated portico, which we used as stage on special occasions,” he said.

The Gabaldon’s center rooms were divided by a collapsible wooden partition that could be folded and converted into a pavilion, he said.

“Gabaldon’s windows were huge … The windows were sashed and made of latticed capiz-tagkawayan. Its façade had those Romanesque Doric-like pillars I’d seen only in pictures like the Parthenon,” Pulgar said.

“Its rooms were big and wide, with lauan floors. Its doors were imposing and made from thick and heavy narra. It had a cavernous silong (basement)—home of the kabag (bats), ahas tulog (snakes), alupihan (centipede) and giant rats. Though it stank in there, we used it as (a) hiding place whenever we were late in flag rites,” he said.

The Gabaldon buildings are “attuned to the tropics,” Villalon noted.

Breezy and cool“The building is breezy and cool. Being inside the restored building today proves that old-style tropical architecture is still the best for our climate,” he said.

There’s a practical sense to ongoing, albeit slow, efforts.

“Instead of being rendered obsolete, old structures can still be recycled for modern academic uses,” Villalon said.

“By restoring classrooms, the DepEd drives home the lesson that patrimony lives and continues to be relevant to our lives. Classes in heritage classrooms provide experiential learning on patrimony with a stronger impact than textbook instruction,” he said.

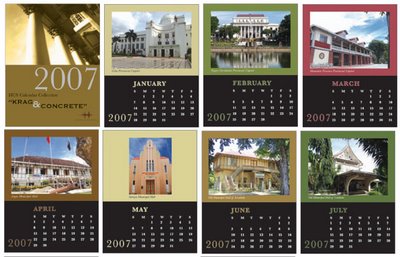

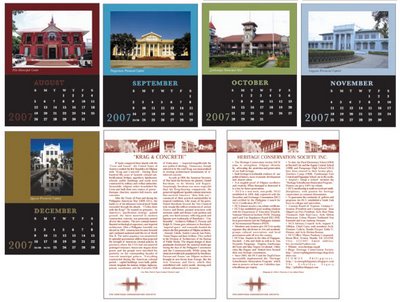

The 2007 HCS Calendar featuring heritage provincial capitols, city halls and municipios, is now on sale. For more information, contact:

The 2007 HCS Calendar featuring heritage provincial capitols, city halls and municipios, is now on sale. For more information, contact: